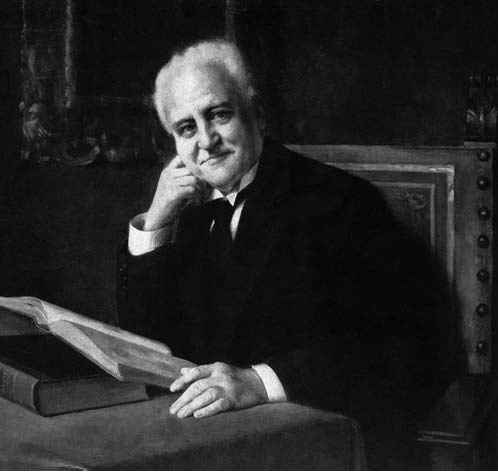

Achille Sclavo (Alessandria, 21 March 1861 – Genoa, 2 June 1930), hygienist, scientist, teacher, was a man of great human qualities, a complex and many-sided personality. He lived at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries when diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, syphilis, typhoid, diphtheria, pellagra and cholera were rife in Italy and hygienic conditions were unbearable in many areas of the Nation. In this period a new professional figure, the hygienist, emerged; Achille Sclavo was the founder of the Italian School of Hygienists. He increased national awareness of the importance of hygiene organizing courses for teachers, military personnel, students, doctors, nurses.

In Siena he promoted the construction of important public infrastructures such as the Vivo d’Orcia aqueduct, a modern sewage system, public baths with doctors’ visiting rooms and laboratories. He promoted the construction of a preschool in public gardens and an open-air primary school, which was later named after him and continues its activities even today. Sclavo provided the first nucleus of a Children’s Hospital on the premises of the city orphanage, with ten hospital beds for children. In the 1930s, a sanatorium, later named Achille Sclavo Hospital, was built outside one of the city gates. We also owe him the promotion of summer courses in Italian language and literature for foreigners. He was also very involved in what are today called non-profit activities, also aimed at including foreigners living in Siena, for example by publishing the fortnightly periodical Fonte Gaia, printed in four languages and distributed in Italy and abroad. Between 1895 and 1903 he began research on serum in Siena and discovered the anti-anthrax serum for carbuncle. In 1904 he founded the Istituto Sieroterapico e Vaccinogeno Toscano Sclavo to produce and market his serum. The company later developed into a world player in vaccinology

Siena was unable to award Dr. Sclavo its highest medal, the Mangia d’Oro, because the prize was only instituted in 1952, however in 1954 it was awarded to Dario Neri (Murlo, Siena, 22 May 1895), administrator of the Sclavo Institute from 1935 to 1944.

In 2001 it was awarded to another Dario Neri (Rome, 1 May 1963), a descendent of Sclavo, a young researcher whose scientific genius continues to keep the Siena flag high in the world. The prize was awarded to Albert Sabin in 1968 and Rino Rappuoli in 1995.

The Sclavo Institute continued to develop new vaccines even after the death of its founder in 1930. In the early sixties it began to produce the poliomyelitis vaccine invented by Albert Sabin and still today is very active in promoting initiatives in favor of developing countries.

Albert Bruce Sabin (Biahystok 26th August 1906-Washington 3rd March 1993). Albert Sabin was of Polish origin, son of a Jewish tradesman. His family emigrated to the USA where he from University College of New York in 1931.

He then worked at the Bellevue Hospital of New York and the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine in London. In 1935, he joined the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. He was director of infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, Cincinnati, from 1939 to 1943. He served in the Medical Corps of the US Army during the second world war. He was awarded the US Presidential Medal of Science, the Medal of Freedom, and the Feltrinelli prize for Medicine of the Accademia dei Lincei, Rome.

His passion for microbiology and virology made Sabin one of the greatest medical researchers of the twentieth century. He was inventor of the attenuated oral vaccine for poliomyelitis, a disease that caused great distress in the 1950s. Because Sabin refused to patent his discovery, the price remained modest and the vaccine could be afforded even in developing countries. The Sabin vaccine quickly replaced the Salk vaccine.

Sabin chose the Sclavo factory in Siena as a suitable place to produce his serum, as well as for communications. In 1968, Sabin was awarded the Mangia d’Oro, the highest recognition of the city of Siena.